A closer look at Beirut’s public space

The School of Architecture’s Visiting Assistant Professor Luisa Bravo and Assistant Professor Lee Frederix reveal their perception of the city and how it inspires their work.

Once considered the Paris of the Middle East, Beirut now strikes the eye with the high density of its concrete structures, the indiscriminate mid-rise and high-rise buildings and the remaining vestiges of bullet-ridden French Mandate houses.

Its architectural landscape is a byproduct of war and reconstruction, both of which were the results of a complex political dynamic. For urban planners, Beirut might not be the most virtuous example, yet it is a challenging one.

“Beirut’s complexity is tangible,” says Luisa Bravo, visiting assistant professor at LAU and at the University of Florence. She first came to Lebanon after the war, when Solidere – the company in charge of planning and redeveloping Beirut Central District – was working on the reconstruction of the Downtown area. “It was not by chance that I came here. I was working on the concept of public space and in Beirut that was the right time to analyze the issue.”

According to Bravo, in Europe the concept of public space is linked to notions of sharing and democracy, whereas in the Middle East this association is not as clear. “The idea of a public space implies that it belongs to everyone, and that everyone has the right to take part in its construction,” says Bravo. “However, the desire to see private interest prevail is predominant, even among the younger generations.”

Bravo recognizes that urban planning is entangled with politics. “In Beirut urbanism is made of elements that intersect and overlap,” she says, “its public space is strongly intertwined with the private one, which tells stories of war and loss and which represents the city’s true spirit.”

The idea that public space belongs to everyone and that therefore everyone should be allowed to participate in its construction is, in itself, a political ideal. Bravo believes that the younger generations in Lebanon still lack a full understanding of the importance of public space but, on the other hand, have strong feelings toward any kind of reconstruction that disregards historical heritage.

“Preserving a city’s cultural identity is of paramount importance,” she says, citing Samir Kassir’s notion of the Arab identity and its failure to come to terms with modernity. “In my lectures, I invite the students to come up with their own alternative ways of thinking, without emulating what is being done in the West.”

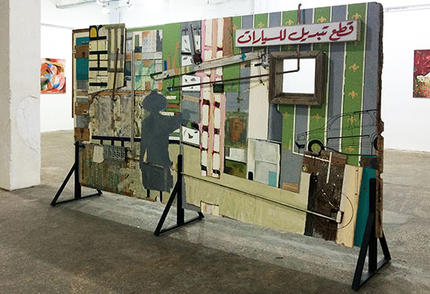

Similar themes have triggered the curiosity of Assistant Professor Lee Frederix, an American artist and designer. In his series Al mamnou3 masmouh, he explores the appropriation of public space and the blurred boundaries between what is allowed and what is prohibited.

“I was amazed to see how shop owners construct improvised objects that they use to assert their ownership over a public space, such as a parking spot in front of their store,” says Frederix. “This inspired me to recreate them in an artistic form.”

The collection, entitled ‘totems of territory’, not only visually recreates the atmosphere of the city, but directly feeds off it through the use of objects collected from its streets.

“At the beginning I had to polish the objects I found, because the effect they produced was altogether too ‘rough’ for the Lebanese taste,” says Frederix. After more than a decade in Lebanon, he now sees his original style as having gone too mainstream.

Frederix also uses the city’s many objects to create alternative mapping systems that talk about gentrification or the shift that Beirut’s neighborhoods witnessed toward increasing property values. In order to give a feeling for the neighborhood he is describing, his work employs pieces found in its alleyways.

Some of the items he collects only make sense after several years. “Once I found a piece that fitted into the other perfectly, like a key. I thought it was meant to be, and I had to make something of it.”

Beirut, with its idiosyncrasies and complexities, is still a jigsaw puzzle able to capture the fascination of professionals around the world.

More

Latest Stories

- LAU Nursing Camp Opens Eyes, Hearts and Futures

- Meet Dr. Zeina Khouri-Stevens, Executive Vice President for Health Services

- LAU Family Medicine Graduates to Benefit from a Partnership With Nova Scotia

- AKSOB Assistant Professor Shares Her Vision for the Future of Learning

- LAU Simulation Models Celebrate 20 Years of Learning, Leadership and Service

- The School of Engineering Hosts the Lebanese Electromagnetics Day

- LAU Stands Out on the Sustainability Scores

- Michael Haddad Walks Again for Climate Change and Food Security